- A legend begins: the Master of Suspense was born 120 years ago today

- Probably the most recognised and highly regarded director in history

- One of the most dissected, discussed and documented filmmakers ever

- Became Britain’s top director within a few years of entering the industry

- He left for America to achieve even greater success and worldwide fame

- Focusing on the best – and worst – books on the Master’s early career

- Separating the wheat from the chaff in a vastly overcrowded literary field

Note: this is part of an ongoing series of 150-odd Hitchcock articles; any dead links are to those not yet published. Subscribe to the email list to be notified when new ones appear.

The British Years in Print, Part 2: Best of the rest

TL;DR: You’ll find the single most essential volume on Hitch here.

Though he had long since scaled film’s commercial peaks, Hitch’s ascendancy to the critical mountaintop didn’t begin in earnest until the 1960s. Ever since, as film historian John Belton attests, Hitch has held an unassailable position as the doyen of film studies (alt):

“The appeal of Hitchcock to the theorist and historian of film is impossible to overstate. To study him is to find an economical way of studying the entire history of cinema.” – Paula Marantz Cohen, The Times Literary Supplement, 5.9.2008

Prior to Hitch, fellow Londoner and iconic filmmaker Charlie Chaplin achieved great success in his homeland before sailing to America and a stratospheric career ascendancy. Also much like Chaplin, Hitch’s distinctive image is recognisable to most, even those who have never seen any of his films. Coincidentally, both men designed their own best caricatures, distilled into simple line drawings. They also share the unique distinction of being, by a very long chalk, the most written-about filmmakers ever. There have been well in excess of 1,000 distinct books alone published about Chaplin, with new ones still appearing regularly; sometimes at the rate of a dozen or so per year. I’d be surprised if Hitch wasn’t on a par, but for all that, there are only a few studies that focus solely on his British work. Careful which you choose though: here, as with releases of his British films, the quality of Hitch books runs the gamut from indispensable tomes to toilet paper.

AFI: Alfred Hitchcock on Filmmaking

To give some indication of the total number, a search for “Alfred Hitchcock” in the Books section of UK Amazon currently brings up around 2,000 results and around 3,000 on the US site. There are at least half a dozen on just one of his favoured themes, the Hitchcock blonde. Of course, not all will be unique titles but conversely, many volumes on the man and his films don’t use his full name, if at all. Many, many published works are covered in Dossier Hitchcock (2011), an extensive bibliography by Norbert Spehner, while you’ll find hundreds of scholarly essays in the Hitchcock Annual and at sites like Academia.edu, JSTOR and ResearchGate.net.

- All about Alfred Hitchcock-Bibliographie (1988) – ed. Hans Jürgen Wulff; almost 3,000 print references

- Looking for Hitchcock: Reviewing Literature on an Icon – Brian McFarlane/SS/GS

- Critical Survey: Writings on Hitchcock – Jane Sloan, introduction to…

As an aside, the same applies to Hitchcock-related documentaries: there are dozens of them concerning the man himself and his American films, but only three noteworthy attempts to cover his pre-1940 career. The Hitchcock: The Early Years featurette accompanies every other home video edition of his ITV-owned films, while Alfred Hitchcock: Films de Jeunesse (1925-1934) appears on two DVDs of Murder! Lastly, the BBC’s Paul Merton Looks at Alfred Hitchcock is currently unreleased but there’s a lo-res upload here. Comparatively slim pickings overall, considering they account for the first two decades of over half a century of filmmaking.

While discussing Chaplin, I must make mention of one of his later talkies that’s absolutely essential for Hitch fans: Monsieur Verdoux (1947). This blackly comic, cynical tale of a gentleman serial murderer is, along with Stanley Donen’s Charade (1963), one of the finest, most Hitchcockian films the Master of Suspense never made. Verdoux is based on an original screenplay by Chaplin, from an idea suggested by Orson Welles. You’ll find all its best quality DVDs here, while HD BD and streaming releases are listed here.

Film scholar Maurice Yacowar (blog) vigorously mounted the first extended, sympathetic evaluation and defence of Hitch’s early career via Hitchcock’s British Films (1977, updated reissue 2010). Yes, defence: for even after Hitch’s critical overhaul and reappraisal of the 1950s and 1960s, the prevailing view of his largely long-unseen British films was deeply disdainful. From the foreword of the second edition of Yacowar’s book:

Film scholar Maurice Yacowar (blog) vigorously mounted the first extended, sympathetic evaluation and defence of Hitch’s early career via Hitchcock’s British Films (1977, updated reissue 2010). Yes, defence: for even after Hitch’s critical overhaul and reappraisal of the 1950s and 1960s, the prevailing view of his largely long-unseen British films was deeply disdainful. From the foreword of the second edition of Yacowar’s book:

“In his pioneering and highly influential Hitchcock’s Films (1965), Robin Wood flatly dismissed Hitchcock’s British films as ‘little more than ’prentice work’ and did not discuss any of them, asking, ‘Who wants the leaf-buds when the rose has opened?’ His conclusion that ‘the notion that the British films are better than, or as good as, or comparable with the later Hollywood ones seems to me not worth discussion’ became the prevailing view, despite Wood’s retraction of this judgment more than twenty years later in Hitchcock’s Films Revisited (1989) as ‘completely indefensible.'”

At least Wood eventually admitted he was, to put it politely, talking out of his hat. But he still didn’t get it completely, as you’ll see in Part 2. Incidentally, Hitch’s actual film apprenticeship was comprised of the 20 shorts and features he worked on in various capacities from the spring of 1920 to the spring of 1925. In complete contrast to Wood, Yacowar’s groundbreaking effort is an immensely readable compendium of his insightful observations on the films themselves. It’s only a pity that having waited 33 years to update his trailblazing book, just another couple more would have enabled Yacowar to base his silents summations on the versions restored in 2012.

In Yacowar’s wake came another winner, Alfred Hitchcock and the British Cinema (1986, reissued 1996) by Tom Ryall who, with a denser, slightly more academic bent, places the man and his work squarely in the context of the industry of the time. Among many other Hitch-related works, Ryall has also authored a fine 2011 biography of Hitch’s contemporary and frequent artistic equal, Anthony Asquith.

When it comes to British Hitch, film historian Charles Barr is as knowledgeable as anyone alive: he’s spent years digging into dark recesses and shining a light on hitherto-hidden corners of the great man’s career. He’s also authored many erudite but eminently readable books and essays on the British film industry, including several on Hitch, but here we’re most interested in just a few of them. English Hitchcock (1999) is exactly what it says: the definitive account of his pre-Hollywood years. From the cover:

“Although Alfred Hitchcock achieved his greatest success and fame in America, he was inescapably English, and the films that he made in his native country before taking up a contract with David O. Selznick are very much more than apprentice work. The Lodger, Blackmail, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes are films of enormous wit and sophistication – masterworks in their own right. However, Hitchcock’s critical reputation has so far been firmly founded on the American films, while his English period has been underestimated and relatively neglected. English Hitchcock rectifies this critical imbalance by providing in an entertaining and elegantly written text a detailed and well-documented reading of the films.”

Review: Scott MacKenzie | review: Tony Williams

English Hitchcock should be the first port of call for anyone wishing to know more about the crucial first half of Hitch’s life and the work he, ahem, executed. If my own series of articles has a spiritual inspiration in print, English Hitchcock is it, as his early films can’t be properly appraised if people persist in watching mediocre quality versions. Without attempting to diminish Hitch’s talent in any way, Barr challenges the auteur theory built up around the Master to give full credit to his influences, source material and writers; more about those below. Time and again, Barr outlines many details, parallels and coincidences, both of each film and in relation to each other, which all serve to profoundly deepen one’s appreciation of their supreme artistry.

English Hitchcock’s only fault is that it’s simply crying out to be updated to include the fascinating discoveries made since it was published, many of which were by the author himself. Then of course there’s the small matter of the inclusion of the Hitchcock 9, as Barr had to rely on the then best available but scoreless and unrestored viewing copies in the BFI Archive. The rear cover of the Barr-penned booklet for Network’s Hitchcock: The British Years DVD box set (2008) promised that a “new revised edition” of his book was imminent, but we’re still eagerly waiting.

Until it is updated, a fine companion to his previous book is Barr’s excellent Hitchcock Lost and Found: The Forgotten Films (2015). Co-written with Alain Kerzoncuf, most of it is taken up with the more obscure side of Hitch’s British output. Stuffed with new and exclusive research, it too is an engrossing read that I can’t recommend highly enough. Essential.

Review: Ken Mogg | review: Henry K. Miller

Hitchcock Becomes Hitchcock: The British Years (2000, reprinted 2008) by Paul M. Jensen is an unjustly unknown work that takes a similar approach to Barr, in thoroughly appraising the validity of Hitch’s entire British career and not just viewing it as a precursor to greater things.

Another great volume for those wishing to dig deeper is Alfred Hitchcock’s London: A Reference Guide to Locations (2009, notes Oct 8-10, review) by Gary Giblin. With truly Sherlockian zeal, the author sets about discovering and documenting many places of central importance to Hitch’s life and films, resulting in a richly rewarding read.

The most unconventional book to cast an eye over Hitch’s British years is the first part of a two-volume graphic novel written by film historian Noël Simsolo with B&W line drawings by Dominique Hé. Alfred Hitchcock: The Man from London and The Master of Suspense (2019–2022) adopt the format of Hitch recounting his life story to the stars of To Catch a Thief, Grace Kelly and Cary Grant, in the wake of Psycho’s unprecedented worldwide success. The second part expectedly covers Hitch’s American career and both are available in English, French and German with the former printed as a single volume.

Now for the bad news: Despite its promising title, Alfred Hitchcock’s Silent Films (2004) by Marc Raymond Strauss is an utter disappointment. It constantly devolves into tedious shot-by-shot accounts of Hitch’s surviving features, as slavishly watched by the author. Given the fact he’s largely relying on old, unrestored VHS tapes and bootleg DVDs, it adds up to little more than a series of interminable descriptions of the same shoddy copies that this series is designed to help you avoid. What’s more, he quotes endlessly from other, much better, film authors and actually makes a virtue of the fact he has done no original research. I kid you not. Unsurprisingly, egregious errors are spread liberally throughout. Printouts of the films’ Wikipedia entries would make a far superior (and more accurate) book. I’m still not joking. When Strauss does venture to offer his own voice, he displays a comprehensive lack of technical understanding of the medium of silent film and even film in general. A distinct, though sadly not unique disadvantage for the author of a book on the subject.

Strauss’s timing was unfortunate in publishing just three years before complete, good quality editions of the films were widely released on DVD. However, he’s still active, particularly in the field of Hitchcock studies, and there’s no excuse for not carrying out a long-overdue update, especially now most of the 2012 restorations are also available. But in its current form, even in such a vastly overcrowded field, it’s one of the most pointless and tortuously written Hitch-related books I’ve ever had the misfortune to come across. How it ever got into print is baffling; even more so is why it remains so and is completely unjustifiable. I’m actually embarrassed on Strauss’s behalf. But don’t just take my word for it: In his review, Tony Williams describes it as a “drudgery to read” and bemoans “the bad scholarship in this dreadful book.” Extremely hard pass. Strauss laudably devotes half of another of his books, Hitchcock Nonetheless: The Master’s Touch in His Least Celebrated Films (2006), to spotlighting seven of Hitch’s more obscure British sound films. But here again, his methodology mirrors the sins of the former work. Another pass.

Criterion Channel: British Hitchcock

Sadly, there are many more similar examples to the above subpar volumes, for instance A Year of Hitchcock: 52 Weeks with the Master of Suspense by Jim McDevitt and Eric San Juan (2009). Its predictable premise is that you watch a Hitch film per week for a year. An unoriginal if nice enough idea but their rendering of it has many flaws, not least of which is that for his British films almost all of their dozens of buying recommendations are bootlegs. There was certainly no shortage of official releases prior to its publishing. I’ve no idea how on earth enduring those chopped-up, cruddy prints is supposed to endear the films to new fans. Even when they do mention legit discs the basic specs are often wrong, so they clearly haven’t actually seen them. Once again, a little cursory research, even a few hours’ googling, wouldn’t have gone amiss.

It seems this film book-writing lark is easy: watch a bunch of ropy bootlegs, quote a lot from better books on the subject, and away you go. And be happy flogging the same old embarrassingly outdated tat decades later, despite having every opportunity to make corrections. There’s no end of them relying on bootlegs as primary sources; Hitchcock’s Ear: Music and the Director’s Art is yet another egregious example. Despite having its moments, for a more comprehensive though also far from perfect book focusing on Hitch’s scores, including his British talkies, get Hitchcock’s Music instead. Its author writes in a clear style, accessible to the layman but makes a few errors, especially in presenting pure assumptions and opinions as fact; for instance see my articles on Spellbound and To Catch a Thief.

- Hitchcock’s Music (2006) – Jack Sullivan | interview, podcast, video | review/#2/#3/#4

- Hitchcock’s Ear: Music and the Director’s Art (2012) – David Schroeder

In reality, it takes a little more effort to become an expert and that’s what a published author on a factual subject needs to be. If you’re going to foist your opinion on folks couched as fact – especially if you plan to make them pay to read it – then exercise due diligence first. This kind of sloppiness really gets my goat; most of the authors of these and other Hitchcock viewing guides blithely, repeatedly, wrongly refer to his British works as “public domain” films. The same applies to many other scholars who ought to know better too. Books, and latterly the internet, are incredible conduits for disseminating information, but falsehoods are spread even more easily: “A lie can travel halfway round the world while truth is pulling its boots on.” But let’s avoid ending on a low note and sneak in a few more goodies:

The British Years in Print, Part 2: Best of the rest

September 2021 update: there’s a highly lauded new kid on the block, mais malheureusement il n’est disponible qu’en français :

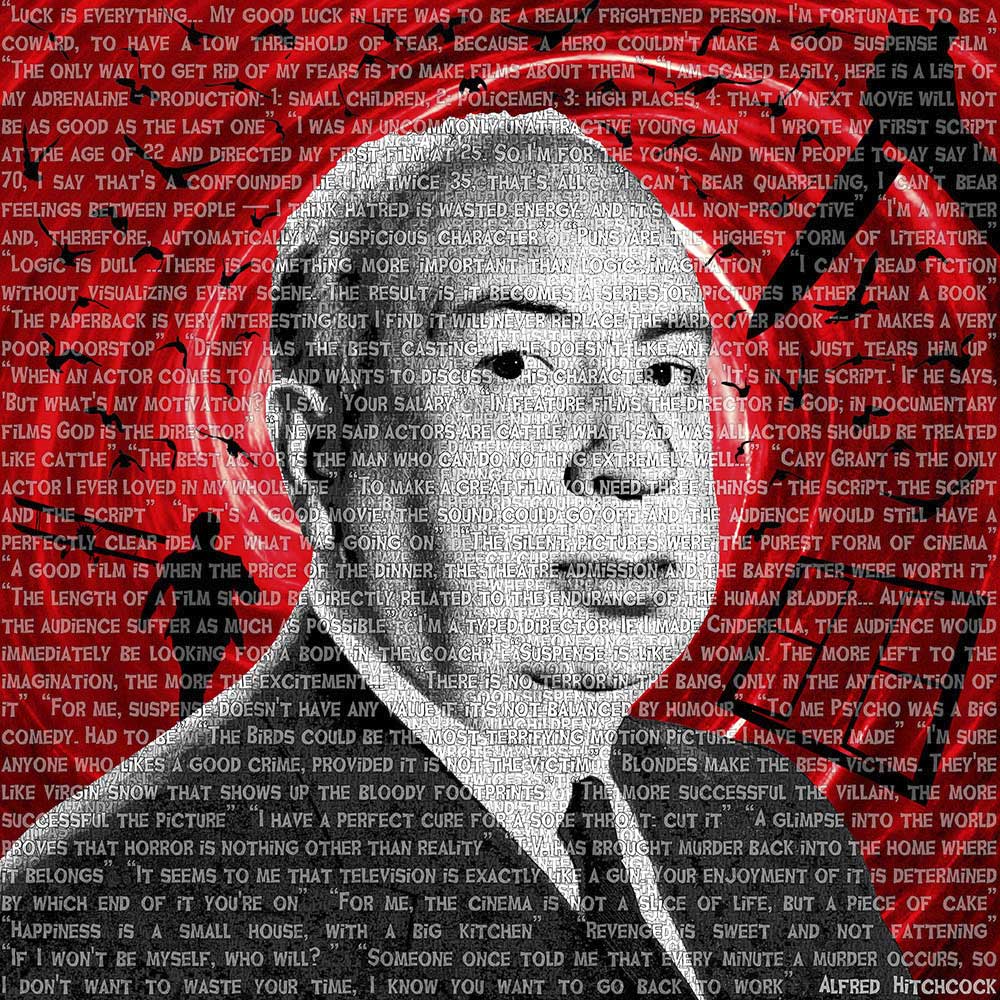

Alfred Hitchcock Quotes ‘Textportrait’ by Olivier Tops, 2017

Related articles

This is part of a unique, in-depth series of 150-odd Hitchcock articles.

Your TL;DR link at the top seems to point to Jamaica Inn Part 3