There is a rare opportunity to see what is at once one of the most brilliant and the most endearing of Soviet silent classics – in the unexpected context of the upcoming Bristol Slapstick Festival

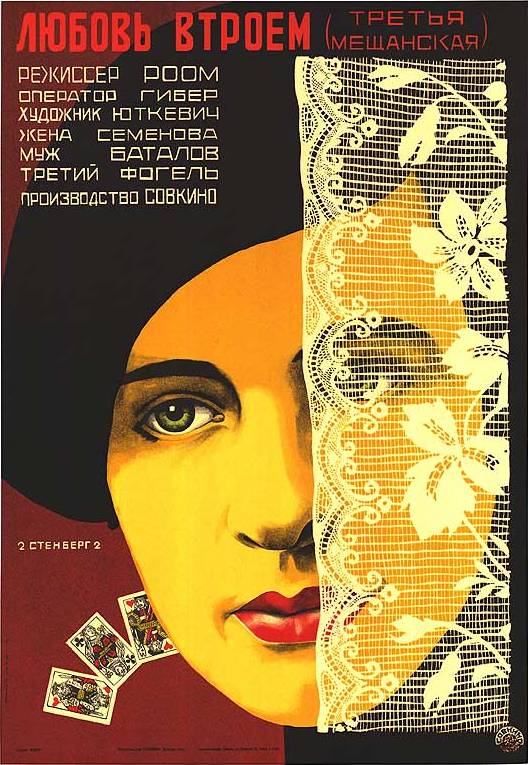

Bed and Sofa (Tretya meshchanskaya, 1927) original Soviet film poster by the Stenberg Brothers, Vladimir and Georgii

Contents

Plot

Bed and Sofa is by no means slapstick, but rather (unexpectedly, given its historic source) a wry and sardonic sex comedy. Kolya (a construction worker engaged on the restoration of the Bolshoi Theatre) and Lyuda live in a one-room basement apartment with a view of the legs of passers-by from its single window. Kolya’s old army chum Volodya arrives in Moscow to take a job in a printing house, but with nowhere to live. Kolya happily offers him their sofa.

Volodya’s courtesy and consideration are in contrast to Kolya’s brusque marital domination, and he soon wins over the initially reluctant Lyuda with presents (a radio and magazines). When Kolya is sent away to work for nine days, the inevitable happens: Volodya moves into the bed. On his return, Kolya storms out: but with nowhere else to stay he soon returns sheepishly to the apartment – accepting that his place is now the sofa.

As the weeks go by, Lyuda is disillusioned as Volodya in turn becomes the inconsiderately demanding spouse The men again swap bed and sofa.

Lyuda announces she is pregnant. Since none of them knows which is the father, the men agree that she must seek an abortion. Lyuda duly goes to the busy abortion clinic, but the sight of the other clients, and of a newborn baby outside the window changes her mind. She is last seen departing Moscow on a speeding train – just as we first saw Volodya arrive. Kolya and Volodya are left with a farewell note – and the choice of bed or sofa.

Production

Sex and marriage were a challenging and constant subject of debate for the new Russian Bolsheviks. While many party-line-toers reckoned that revolutionary energies should not be diverted into such private trivia, the brilliant and sophisticated pioneer revolutionary and feminist Alexandra Kollontai recognised that “sexuality is a human instinct as natural as hunger or thirst.” The bourgeois and religious traditions of marriage and family were obviously rejected, in favour of civil marriages, and as late as 1925 there was a (failed) attempt to introduce a bill altogether eliminating distinctions between registered and unregistered marriages. Divorce was an effortless formality. The concept of illegitimacy was eliminated. One consequence was a vast rise in the numbers of abandoned and homeless children, already unmanageable after the Revolution and Civil War; and as one measure to contain it, in 1920 abortion was legalised for the first time in any European country.

With the Stalinist thirties and a fall in the birth rate, the state took a tighter hold over marriage and sex. In 1934 homosexuality, decriminalised in 1922, again became an offence, with the approval of Maxim Gorki, who declared, short-sightedly perhaps: “Destroy the homosexuals: fascism will disappear”. Abortion was again prohibited, or at least made extremely difficult. Russian moral codes were firmly and durably redefined.

Bed and Sofa tellingly reflects this period of domestic moral confusion, in which women were the least favoured element. The ideal of the new Soviet woman was as an independent and wholly participating member of society. The frequent reality was domestic enslavement and informal and impermanent conjugal alliances that left the woman with a child and little financial claim on the father. The ideal of the working socialist woman was undermined by massive female unemployment. So we can hardly blame poor Lyuda if she falls short of the bolshevik ideal, being unemployed and spending her time washing, cooking, mending, making jam and browsing movie magazines.

The film’s Russian title is Tretya Meshchanskaya (Third Meschanskaya), the name of a then actual Moscow Street. The word “meschantsvo” however had come to be associated with petty-bourgeois vulgarianism and materialism – reflected in the muddle of ornaments and possessions in the apartment. The Russian secondary title was Lyubov Vtroyom (Triple Love), which is a deliberately close but not exact echo of the Russian term for ménage à trois – Bak Vtroyom (Triple Marriage). This has led commentators to discuss the story as a ménage à trois, which it is distinctly not: it is in fact a rivalrous romantic triangle, in which there are only exclusive couplings, never the complete tripartite relationship of the ménage à trois. (In his meticulous and invaluable study of the film Julian Graffy traces Russian fascination with such relationships back to Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s 1863 novel What is to be Done?, and exemplifies the famous relationship of Vladimir Mayakowsky with Osip and Lili Brik.

Immediately before embarking on Bed and Sofa, the director, Abram Room, and writer Viktor Shklovsky had worked with Mayakowsky and Lili on the short film Jews on the Landi (Evrei na zemle, 1927); but Shklovsky specifically stated that the story was inspired by a real case of the confusion of two men over which had impregnated a woman.) Bed and Sofa and the German Bett und Sofa provide the ideal title: the two pieces of furniture at every point symbolise the characters’ changing sexual/romantic fortunes.

Life into Art: Laying Bare the Theme in Bed and Sofa – Rimgaila Salys

The film had a mixed reception in the Soviet Union. Some saw it as an unprecedented commentary on social-sexual mores: others charged it with pornography and deplored its open ending – exceptional in the scripts of Shklovsky, who generally favoured neat moral closures. The ending is indeed enigmatic. Lyuda, we can see, has finally extricated herself from male domination and has a chance to make a new independent life for herself and her child. But what will happen to Kolya and Volodya? The pattern of “Triple Love” should now demand their coupling, and there have been attempts to put a homosexual slant on the final scene, with the two of them left alone to choose between bed and sofa: “Shall we have some tea?”, asks Kolya: “Is there any jam left?”. Lyuda is the past, and what we already know of them does not encourage hope that they will have the enterprise to go in search of new partners.

The American academic Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (1950-2009) originated the phrase “male homosocial desire” which fits rather well the Russian masculine comradeship of army and bathhouse. When Kolya introduces Volodya to Lyuda he tells her “He’s my friend. In the war we were covered with one greatcoat!” There are four kisses in the film. Twice, on departing for work Kolya gives Lyuda a perfunctory peck. His lingering mouth-to-mouth kisses are reserved for Volodya (though the second time Volodya has his eyes shut, and thinks it’s Lyuda). No doubt the boys will work out new permutations of bed and sofa.

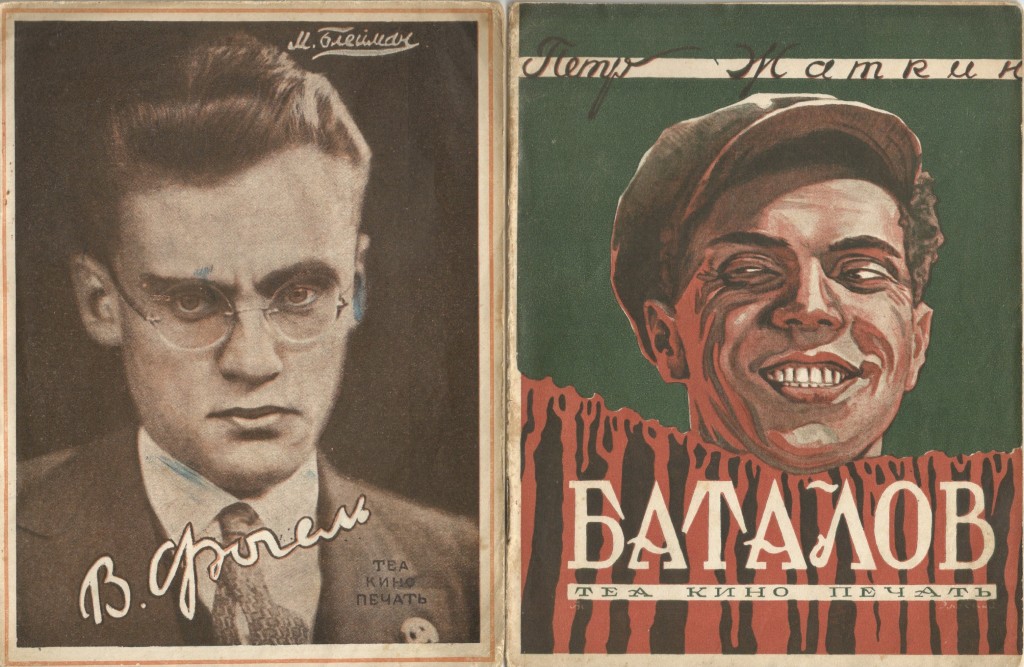

The characters are given the full names of the actors who play them. Kolya is Nikolai Batalov, a leading actor of the Moscow Art Theatre whose comparatively few film roles are all memorable: they also include Aelita (1924), Mother (Mat, 1926) and the first Soviet talking film The Road to Life (Putyovka v zhizn, 1931). Batalov was to die of progressive tuberculosis in 1937 at the age of 37. Volodya is the 24-year-old Vladimir Fogel, the suave and charming comic actor who also stars in several of the most famous Soviet comedies, the aforementioned The Road to Life, The Girl with the Hatbox (Devushka s korobkoy, 1927) and Chess Fever (Shakhmatnaya goryachka, 1925). Fogel, the victim of private psychological torments, committed suicide three years after Bed and Sofa. Lyudmilla Semyonova (Lyuda) was primarily a stage actress, but appeared intermittently in films until 1961, and died in 1990, at 91.

The director Abram Room was a Latvian Jew who had moved from medicine to theatre, and worked with Meyerhold’s experimental theatre before embarking on films. After Bed and Sofa he was widely ranked with Pudovkin, Eisenstein, Kuleshov and Dziga Vertov in the top echelon of Soviet directors, but though he continued to direct consistently until the 1960s, few of his later films are now remembered. This was one of six scripts written by Viktor Shklovsky (1893–1984) in 1926–7: a friend of Mayakowsky and Osip Brik, he was to remain a powerful influence in the Soviet cinema as critic, historian and writer for the next half century.

In a revealing interview with Kino magazine before starting the film, Room was clear in their intentions, urging the need for a film that should be “condensed and concentrated, and where everything is staked on the playing of the actors and the maximum invention of the scriptwriter, the director and the cameraman. The catchword for such a picture is aesthetic economy…

The subject is condensed and enclosed in a small space of time, a single room, and Moscow exteriors. With this baggage the three characters embark lightly on their journey through the film…

Love, marriage, the family and sexual morality are urgent contemporary topics… but have not yet been tackled at all by the cinema. Or, more exactly, the Soviet cinema has not yet approached them in earnest, and if it has touched on them by chance it has shown a shallow, primitive ‘delicacy’… so far all we have heard is sniggering, baby-talk and lisping. We must start to use real words.”

This frankness they achieve (even though Volya and Lyuda share the bed fully dressed except for a shoulder exposed by a slipping blouse). Few films before or since have ever come so close to their people and their feelings. Bed and Sofa is a rare work that rewards intense concentration. Every shot, detail, gesture, glance, reflection draws us deeper into these three likeable, imperfect people and their interaction. The critic of the avant-garde film magazine Close-up in 1927 got it right: “Our advice to everyone who can see it is to see it at all costs”.

See Bed and Sofa screening at Bristol Slapstick 2016

Home video releases

The film itself was first issued on DVD in the US with English-language intertitles, no foreign-language subtitles and an audio commentary by Julian Graffy, author of Bed and Sofa: The Film Companion (2000, review). It’s coupled with Chess Fever (1925, 28 minutes), a great Russian comedy short also starring Vladimir Fogel, and with the same language specs. The disc has been reissued unchanged on DVD-R; both releases are NTSC region 0, meaning they’ll play anywhere in the world. There’s also a French DVD, less subtlety titled Ménage à trois, with the same score as the US discs and coded PAL region 2 with Russian intertitles, and optional French subtitles.

Check out these in-depth articles on the scoring of the DVD:

- Making Silents Sound Good: Rodney Sauer on Scoring Bed and Sofa

- Bed and Sofa cue sheet by Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra

Musical

In 1996, Bed and Sofa was adapted as an award winning musical which has received regular US and UK revivals, most recently in 2015 (more, more, more).

- Bed and Sofa/alt (1996) – Polly Pen and Laurence Klavan | Broadway Licensing

Related articles

- New Eisenstein Biopic: Greenaway Goes Loco in Guanajuato

- Win tickets to the test screening of brand new silent film London Symphony!