Early Reissues

- As the Little Tramp’s popularity grew, so did his films’ scale and complexity

- They became longer and more sophisticated as he moved to bigger studios

- Each time Chaplin moved on, earlier studios recut and reissued his old films

- Were countless worldwide recuts and compilations but most no longer survive

- Some significant early reissues throw up a number of fascinating collectibles

This is part of a unique, ongoing series covering Chaplin’s life and career.

Contents

- Recycling the Tramp

- Keystone reissues

- Essanay compilations

- A Burlesque on Carmen (1915)

- The Essanay-Chaplin Revue of 1916

- Chase Me Charlie (1917)

- Triple Trouble (1918)

- Charlie Butts In (1920)

- Van Beuren Mutuals

- Further reading

- Related articles

Recycling the Tramp

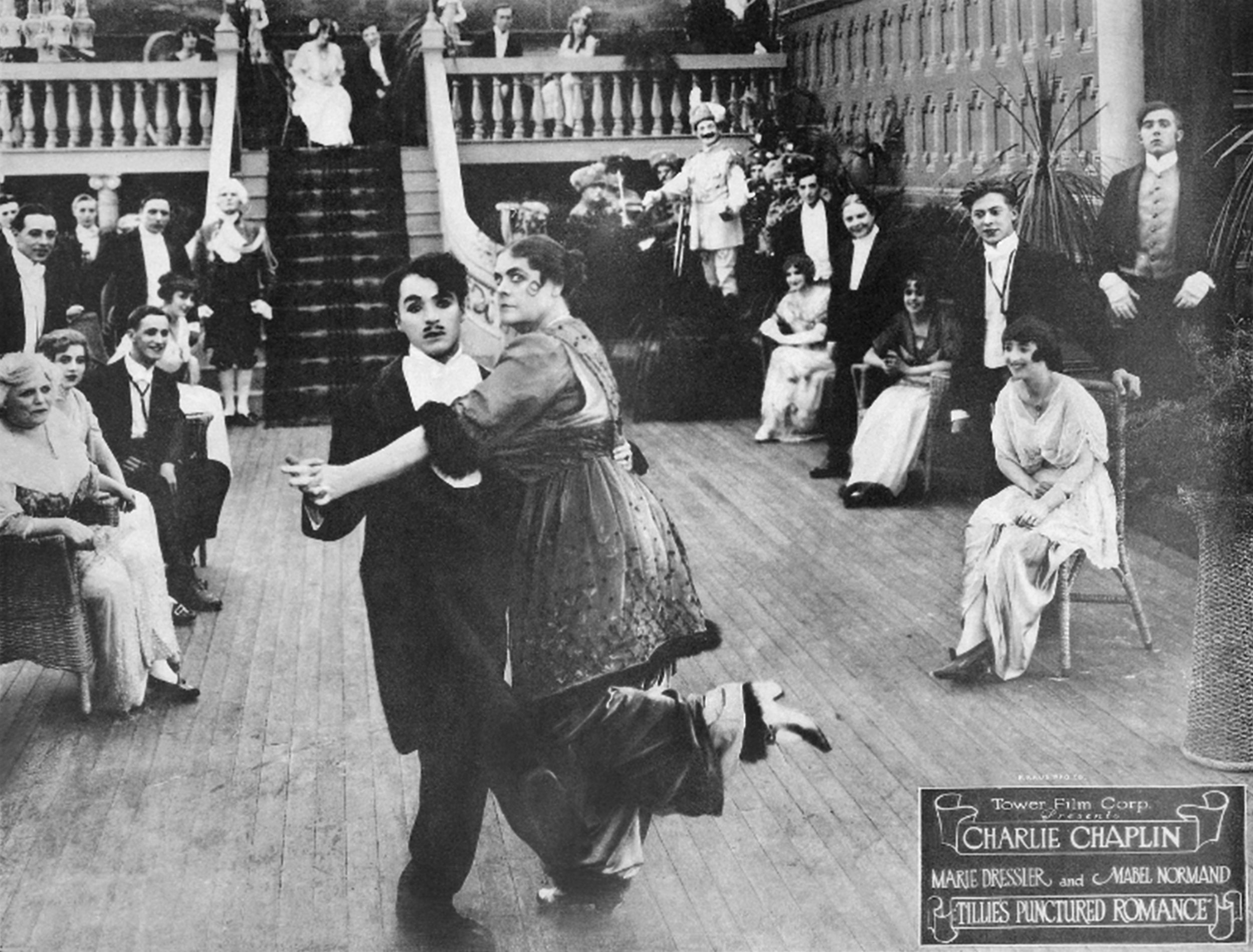

Motion Picture News advert; landscape. Though original publicity for Chaplin’s first feature headlined Marie Dressler, all subsequent reissues in all media have foregrounded him, usually as the Little Tramp, most often omitting his co-stars entirely.

Before dealing with the restored Keystones, Essanays and Mutuals, it would be a shame to overlook some earlier versions of those films that are still very desirable. Once he left them, each of Chaplin’s first three studios recut, rearranged and retitled numerous Chaplin-unauthorised reissues of their holdings to cash in on his ever increasing popularity. Usually they tried to pass them off as brand new product, hoping to fool a public hungry for more of the Little Tramp.

Successive owners of the films swiftly replaced any previous owners’ branded credits and intertitles; consequently the majority of original examples are now lost, causing a headache for restorers. However, some of the most significant, widely released examples are extant in one form or another and available to buy. Many compilations contain rare, otherwise unissued footage and soundtracks, making them essential viewing for the dedicated fan or scholar. Eventually of course, Chaplin himself re-edited and scored his First National shorts for reissue, with three of them being compiled into The Chaplin Revue (1959).

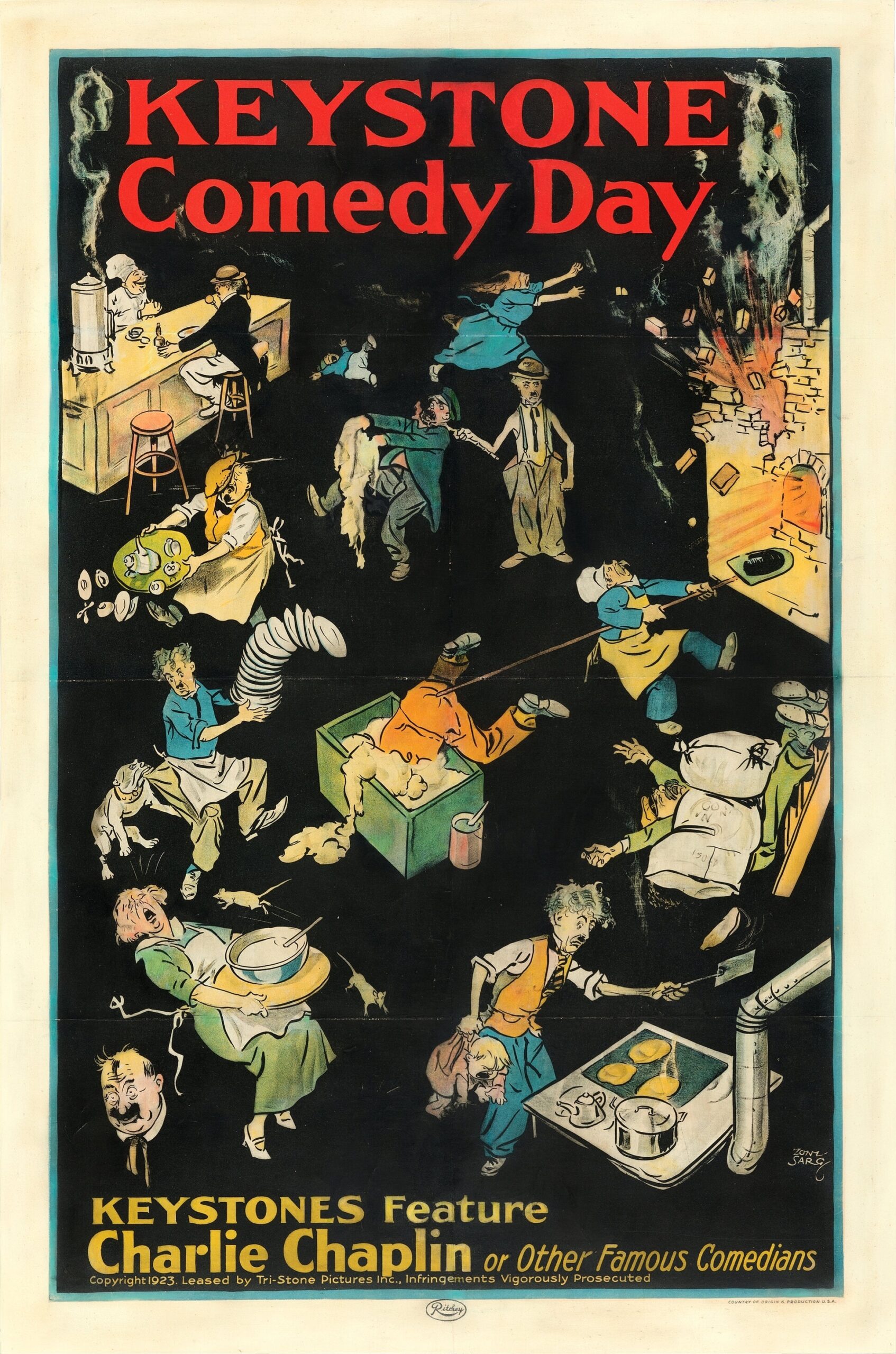

1923 US poster by Tony Sarg. “A theater owner in Atlantic City, New Jersey started holding a “Keystone Comedy Day” in 1923, which proved to be very popular and soon expanded into other cities through the rest of the 1920s.”

Keystone reissues

Almost from the start, Chaplin’s three dozen Keystones, all made and released during 1914, were especially severely reused and abused. Literally hundreds of battered, bootlegged, variants constantly made the rounds just within their first few decades of existence. They were endlessly retitled too, with most having half a dozen or more documented variants. There were even some early compilations of the shorts, such as Triangle’s now-lost Mixed Up (1915). Other compilations, such as the faux documentary Charlie’s Life (1916), “mixed up” footage from other studios and were presumably outright bootlegs. Most of the unrestored Keystones are all but unwatchable, and the majority now come with awful needle-drop scores of random old public domain music. They can be easily found via the likes of YouTube or the hordes of cheap public domain Chaplin DVDs.

“Guaranteed new prints from original negatives which we own and control.” And ultimately worked to death. Grrr…

For all that, the unrestored Keystones are still worth a look, even if only to better appreciate just how far we’ve come with the brilliant restored versions. Also, for the serious fan or scholar, many of them reveal some interesting surprises and help deepen our understanding of how Chaplin’s films – and silents in general – were regarded and treated throughout the 20th century and well into the current one. All the retitled shorts fell into semi-anonymous, interchangeable disarray, but just one remained a known quantity in its own right: Tillie’s Punctured Romance, the biggest of them all.

The studio’s only feature length film, it starred veteran comic stage actress Marie Dressler in her first onscreen appearance, with support from Chaplin and almost every other notable actor on the studio’s books. Tillie was a huge success on release and although she went on to suffer many of the same vicissitudes as her shorter siblings, her name and body remained, for the most part, more or less intact. In fact, as a stand-alone or supporting feature she’s been regularly remodelled and exhibited her whole life. Not bad going for an old gal. I’ve covered her amazing story in more detail here:

Charlie Chaplin Collectors’ Guide: Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914)

A Burlesque on Carmen (1915)

One of the best known of all the early recuts – sadly perhaps even more so than the Chaplin original which spawned it and the two films which spawned that. All are dealt with separately here:

Charlie Chaplin Collectors’ Guide: A Burlesque on Carmen (1915)

The Essanay-Chaplin Revue of 1916

Following a failed legal attempt by Chaplin to block their mangling of his original Carmen cut, Essanay continued with a series of such films. One of them, The Essanay-Chaplin Revue of 1916, was just a lazy splicing together of the 1915 shorts The Tramp, His New Job and A Night Out in their entirety. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this production is that this publicity image shamelessly plagiarised one of celebrated American artist Norman Rockwell’s most iconic paintings. People in a Theatre Balcony, aka Charlie Chaplin Fans, graced the cover of the October 14, 1916 edition of The Saturday Evening Post, just a week before the October 21 release date of Revue. A rip-off advertising a rip-off – how fitting.

Revue‘s similar but more obscure immediate predecessor was Charlie’s Stormy Romance (1916), a seven-reeler which apparently also included non-Chaplin clips from Mary Pickford and Francis X. Bushman. While Bushman was one of Essanay’s biggest stars alongside Chaplin, Pickford never worked for the studio, so it was very likely a bootleg.

It seems as though every other one of these early compilations, if not actually featuring “Revue” in the title, were referred to as such in publicity. A typical example is the advert below. Further complicating matters is Chaplin’s own aforementioned, similarly monikered compilation.

Chase Me Charlie (1917)

A little more effort was put into the seven-reeler Chase Me Charlie, an entirely British concoction featuring highlights from nine of Chaplin’s Essanays. It was ‘written’ by Herbert Langford Reed, who also directed some new linking scenes which possibly included actor Graham Douglas impersonating the Little Tramp. (Records conflict on this; get in touch if you know more.) Langford Reed is now best remembered as an author of limericks and other witticisms, and a somewhat controversial Lewis Carroll biography. According to the BBFC and BFI, Chase Me Charlie seems to have enjoyed UK re-releases in 1933 and 1951, before disappearing here altogether.

It was released in the US in 1918 (MPW May 4, p.664), albeit edited down to a five-reeler. That version resurfaced in 1959, this time with a new synchronised orchestral score by Elias Breeskin (one sheet and half sheet posters; lobby cards, variant). It also featured narration by Teddy Bergman, who later changed his name to Alan Reed and became best known as the voice of Fred Flintstone. In 1966, low-budget exploitation filmmaker Samuel M. Sherman reissued the film yet again but retitled it Chaplin’s Art of Comedy. He retained the Breeskin score but replaced Bergman’s comic narration with newly written dialogue, narrated by Dave Anderson, and added a short ‘Hollywood then-and-now’ prologue. Then he cheekily credited himself as its sole producer, writer and director!

Long after enjoying worldwide theatrical release, that version eventually appeared on home video but to coincide with its 1966 reissue, Breeskin’s score was released on LP. From the rear sleeve: “The unique, nostalgic musical moods of the Chaplin’s Art of Comedy score are excellent backgrounds for your home movie shows. Play this record with your favorite silent slapstick comedies (especially those with Charlie Chaplin) and movies you film yourself.”

- US: Pizor VHS (198-)

- Image DVD (1999) trailer download

- Mainstream LP/MP3 (1966)

US 1970 re-release poster (trade ad, #2, CC Archive)

Triple Trouble (1918)

Now we come to another well known Chaplin compilation reissue. Triple Trouble is a two-reeler (23min) consisting of outtake footage from Work (1915), Police (1916) – some of it flipped to ‘disguise’ its origins, and Life, Chaplin’s abandoned first feature length comedy. As with A Burlesque on Carmen, Triple Trouble was supplemented with newly shot, non-Chaplin scenes directed by Leo White. Unfortunately, the sum of Triple Trouble‘s parts is greater than the whole, as its storyline is as incoherent as other such cash-ins. Its real value lies in its rare footage, as surviving outtakes from Chaplin’s Keystone and Essanay periods are extremely scarce. His original intention for its extended flophouse sequence remains a subject of hot debate.

This US Essanay trade ad’s claims are a total lie: it’s as rehashed as they come. Motion Picture News, August 3, 1918, p.704-705

Just prior to Triple Trouble’s release, Chaplin took out a trade magazine advert vociferously objecting to its existence and Essanay’s disingenuous publicity touting it as new product. However, his attitude apparently softened over the years, as 50 years later he thought enough of it to include it in his official filmography, published in his autobiography. Triple Trouble can be found in all the restored Essanay collections as an extra alongside Carmen. David Shepard gave his 1990s restoration a piano score by Eric James, while its latest HD incarnation features a score by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

- My Autobiography (1964) – Charlie Chaplin | It | De | Fr | Es

- Making Music with Charlie Chaplin (2000) – Eric James

As with Carmen, the latest BFI set includes an exclusive second recut version, Charlie’s Triple Trouble (1948, 16min), one of 12 Chaplin shorts re-released in the UK by Cavendish Pictures. Like the rest, it has no actual musical score but is accompanied by a synchronised soundtrack featuring sound effects and a comical commentary. It was written by Ted Kavanagh and spoken by comedian Tommy Handley, the duo behind the incredibly popular radio series It’s That Man Again aka ITMA (1939–1949). The indisputable voice of wartime Britain, Handley had another Chaplin connection with the Hitler-baiting B-side of his 78rpm record, “The Night That We Met in a Black-Out”/”Who is That Man… ? (Who Looks Like Charlie Chaplin)” (1939, audio, lyrics/lyrics).

Chaplin’s protest telegram, alongside an ad for a “Genuine” comedy. Moving Picture World magazine, August 10, 1918, p.758-759

Charlie Butts In (1920)

The last Essanay compilation of significant interest is Charlie Butts In, essentially a one-reel (10min) version of A Night Out (1915), his two-reel second short for the company. Mostly comprised of curious alternate takes, it also opens with a unique, funny scene of the Little Tramp conducting a brass band at Mer Island. It’s only available in the latest Essanay collections from the US, UK and France.

Van Beuren Mutuals

Chaplin’s 12 Mutual shorts were reissued numerous times by a handful of different owners during the 1910s and 1920s. In 1932, they were acquired by the Van Beuren Studios who over the next two years reissued them at sound speed, 24 frames per second, with new synchronised soundtracks. These consisted of specially composed hot jazz scores by bandleader Winston Sharples and composer Gene Rodemich, played by many top session musicians along with over the top sound effects. Van Beuren were primarily known for animation and they scored the Mutuals exactly as they did their cartoons, with ‘Mickey Mousing’ a-plenty.

Additionally, and problematically for restorers, Van Beuren replaced the title cards and removed most of the remaining intertitles, creating many jump cuts and some difficulties in following the action. Nonetheless, their USP is the soundtracks and despite being tinkered with and sped up, they’re still generally very effective. These versions have remained in circulation, latterly in the public domain, ever since and are many fans’ fondly remembered introduction to the films. You can get an idea of what the much-duped versions are like from this low quality copy of The Count.

In 1938, the Van Beurens were spliced together by new owners Guaranteed Pictures for distribution as three feature-length compilations: the Charlie Chaplin Carnival, Cavalcade and Festival, which are available on a low quality region 0 DVD. Unlike the thoroughly dissipated Keystones and Essanays, early generation materials on the Mutuals remained in good shape, as they have a continuous chain of title since their first release. While working at Blackhawk Films in the early 1970s, David Shepard set up their acquisition of the library containing the Van Beuren/Guaranteed compilations, along with some negatives and other material.

He and Bill Lindholm then carried out some minor restoration on them. As no original Mutuals’ main title cards are known to exist, Shepard created “ones in period style that… were designed by me in 1974 and are purely conjectural, although they are nice.” At the same time, they copied the intertitles from a set of mid-1920s reissues. These titles, with some additions, then appeared on all versions of the films until the 2013 restorations. Remastered from 16mm at 24fps, these versions of the Van Beurens were initially issued in 1975 on 8 and 16mm film. Later, they appeared on four LaserDiscs as Charlie Chaplin: The Early Years (Republic Pictures, 1991). Those versions, dishonestly copied directly from the LaserDiscs themselves, are available in a 2-DVD-R set (Grapevine, 2010).

US 1933 sound reissue poster (alt)

Shepard worked on the Van Beurens again in 1984, this time remastering them from full aperture 35mm at 20fps. The jazz soundtracks were then slowed down to match and returned to their original pitch using an Eventide Harmonizer. These were also released in three volumes on LaserDisc as Chaplin: Lost and Found (Image, 1988) and VHS as Charlie Chaplin at Mutual Studios (Kino 1990). They’ve since been pirated once again, this time in a 3-DVD-R set (Reelclassicdvd-r, 2010).

The 1970s versions are rougher looking and cropped on the left edge to accommodate the optical soundtrack. The latter versions, while having better image quality, are missing some footage compared to the earlier versions and due to the alterations have slower, occasionally unsynchronised audio. If it’s image quality you’re after, you’d be better off with the Mutuals’ more recent restorations. If you’re mainly in it for the Van Beuren scores, the 1975 versions, now on Grapevine, are the overall best ones to get. Ignore spurious claims by either DVD label to have made any improvements to these films themselves: all they’ve done is copy the LaserDiscs without authorisation and chopped off their original credits in a clumsy attempt to hide the source. Both DVD sets are region 0/NTSC, so will play anywhere in the world.

More recently, six of the shorts (The Cure, The Floorwalker, The Vagabond, Behind the Screen, The Fireman and The Rink) have appeared as SD extras on Umbrella’s Australian BD of Chaplin (1992). And in the latest Mutual restorations, The Pawnshop (1916) has had its Van Beuren score faithfully recreated by Eric Beheim and Robert Israel.

- Reelclassicdvd-r 3-DVD-R (2010, reissued 2019) info

- Grapevine 2-DVD-R (2010)

- Umbrella BD (2017) – 6 shorts in SD

Further reading

The dishonest free-for-all of reissues designed to fool the public right from the early years of the film industry is a fascinating area of study. Distributors faced legal and moral challenges from many quarters, not just the likes of Chaplin, but they ploughed on undeterred as the profits were just too great. If you’d like to explore further, these two books are the best place to start. Both are meticulously researched, covering both Chaplin and his contemporaries in considerable depth.

- Hollywood Vault: Film Libraries before Home Video (2014) – Eric Hoyt

- Coming Back to a Theater Near You: A History of Hollywood Reissues, 1914-2014 (2016) – Brian Hannan

Photoplay, August 1918

Grateful thanks to David Shepard (1940–2017) for his help with this article. And a life well-lived, in pursuit of preserving our past and spreading love, joy and laughter.

Related articles

This is part of a unique, ongoing series covering Chaplin’s life and career.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ipmgroup/2IHMUTR4NJHRFAOGZLDZQVQP2Y.jpg)