British Law

- Iconic director who made many of the most revered and critically acclaimed movies of all time

- ALL of his films are copyrighted worldwide but many falsely claim the earliest are public domain

- Pirates and thieves have exploited this popular myth, leading to countless terrible quality bootlegs

- The proliferation of illicit copies adversely affects restoration and release of official editions

- Every Hitchcock film or TV programme on streaming sites and not officially licensed is pirated

Note: this is one of 100-odd Hitchcock articles coming over the next few months. Any dead links are to those not yet published. Subscribe to the email list to be notified when new ones appear.

As stated previously, the copyright status of Alfred Hitchcock’s films is easily the most misunderstood area of his entire legacy. Especially of those from the first half of his near-60-year career. Though he’s one of the most studied and written-about filmmakers in history, only a scant few authors have skimmed over the subject. Even of those that have, their findings are completely incorrect or at best incomplete. Some even make the very same point about others’ inaccuracy while then going on to perpetuate more misinformation themselves!

Well, not this time: historian Nick Cooper has produced the first comprehensive, thoroughly researched survey of the historical copyright status of every single film from the Master of Suspense. Parts 1 and 2 explain British and American copyright law, while parts 3 and 4 detail the copyright history of each British and American film from première–present day.

As with most actual legislation, copyright law seems like some arcane branch of alchemy to most people. Many seem to believe that copyright is either perpetual or near-perpetual – often attributed to the actions of the Disney Corporation! – or else a lot shorter than it actually is. There is also often confusion over the copyright status of a work in different territories, especially if it is – or at any point was – public domain in the United States. Only a few authors get it right. Even the term “public domain” itself is open to misinterpretation. This article demystifies the concept of copyright in different jurisdictions, with specific reference to the films of Alfred Hitchcock.

Contents

- The Copyright Act 1911

- The Copyright Act 1956

- Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

- The Duration of Copyright and Rights in Performances Regulations 1995

- Crown Copyright

- Related articles

The Copyright Act 1911

The legislation in place when Hitchcock started working in films in the UK was the Copyright Act, 1911 (the “1911 Act”). This was actually an “Imperial Copyright,” applicable to all countries in the British Empire, and which was also voluntarily adopted by the Dominions of the Commonwealth. It was formulated in response to the UK becoming a signatory of the Berne Convention on copyright, which set minimum copyright terms for most works, and other related standards.

In the 1911 Act, narrative films were treated as both “dramatic works” and a series of still photographs, while non-narrative films were merely the latter. In broad terms, anything that was fictional or a dramatic recreation was both a dramatic work and a series of photographs, but simple footage of real events was only a series of photographs.

Under the 1911 Act still photographs – including those forming part of a film – were protected for 50 years from the end of the year in which the original negative was created, and in the first instance the copyright was owned by whoever owned the camera. In the context of film-making, that meant that the first owner of the copyright was whoever owned the film camera, which would invariably be the studio and/or producers of the film. If a camera was hired in for a specific project, there would need to be a clause in the associated contract transferring the ownership copyright – known as an “assignment” – to the studio/producers. Similarly, for on-set still photographs taken for continuity or publicity purposes, if the still camera was the property of the studio/producers, the copyright would also be theirs, but if the camera was owned by someone else, there would also have to be an appropriate written assignment.

For the purposes of a film as a dramatic work, the copyright term was set as 50 years from the end of the year in which the first co-creator[1] to die did so. If, however, any co-authors were still alive at the end of this 50-year term, copyright protection would be extended until the end of the year in which last that of them died.

In the first instance ownership of the copyright would be shared equally between all co-creators, although naturally in practice contracts would include the necessary assignments to the studio/producers.

Although not specifically stated in the legislation, it was widely accepted that co-creators in the case of narrative films were the credited director or co-directors, and writers or co-writers, including the writer or writers of any original source text (e.g. novel, play, etc.). Where one or more co-creators died before a film was released, the division of initial copyright ownership was not affected, but the 50-year posthumous term would only be based on those who were alive at the time the film was released.

Examples

- Always Tell Your Wife (1923): The first co-creator to die was co-writer/co-director Seymour Hicks, in 1949, giving a 1911 Act copyright term expiring at the end of 1999, by which time the other co-creators – i.e. Hitchcock and Hugh Croise – had already died themselves.

- The 39 Steps (1935): The writer of the original novel, John Buchan, died in 1940, suggesting a 1911 Act copyright term expiring at the end of 1990. However, as script co-writer Charles Bennett did not die until 1995, protection would instead have expired at the end of that year.

- Sabotage (1936): The writer of the original novel (The Secret Agent – not related to the Hitchcock film of the same name!), Joseph Conrad, had already died in 1926. The 1911 Act term was therefore calculated from Hitchcock’s death in 1980 to the end of 2030, by which time all the other co-creators – i.e. Anthony Armstrong and Charles Bennett – had already died.

These rules – as well as all subsequent legislative changes – applied to all of Hitchcock’s films, regardless of their place of production, with the exception of the French-language shorts Bon Voyage and Aventure Malgache, which will be dealt with separately later.

Had there been no subsequent change to UK copyright law, and the terms of the 1911 Act remained in force, Hitchcock’s films would have started progressively falling into the UK public domain at the end of 1981 – with The Manxman – until a final batch of 16 films at the end of 2030, those being where Hitchcock himself was the first co-creator to die, and no co-creator had lived beyond that year.

The Copyright Act 1956

In the event, long before any of Hitchcock’s films could have fallen into the public domain under the terms of the 1911 Act, it was largely replaced by the Copyright Act, 1956 (the “1956 Act”). In this new legislation the term of posthumous copyright of a dramatic work was changed to run for 50 years from the end of the year in which the last co-author to die did so, and this applied retrospectively to all existing works created before it became law on 1 June 1957. Overnight this increased the terms of protection for almost all of Hitchcock’s films, meaning that the earliest that any of them would enter the UK public domain would be 2030 – based on Hitchcock’s own death – right through to the end of 2061 for Rope (1948), based on co-writer Arthur Laurents’s death in 2011. Only two films – The Ring (1927) and An Elastic Affair (1930) – were unaffected, and retained the same protection as under the 1911 Act, as Hitchcock was the sole credited writer and director on both.

Examples

- Always Tell Your Wife (1923): Protection increased to the end of 2030, i.e. Hitchcock’s death plus 50 years.

- The 39 Steps (1935): Protection increased to the end of 2045, i.e. Charles Bennett’s death plus 50 years.

- Sabotage (1936): Protection increased to the end of 2045, i.e. Charles Bennett’s death plus 50 years.

Under the 1957 Act films ceased to have a secondary protection as a series of still photographs, and were instead protected as films for 50 years after the end of the year in which they were registered under Part III of the Cinematograph Films Act, 1938 (one of the “quota” acts), or – if not registerable – 50 years after the end of the year in which they were released. This “film copyright” has given rise to much confusion and even wilful misinterpretation in recent years, with it being used as an argument that films more than 50 years old are no longer protected by copyright in the UK. This ignores the fact that the vast majority remain separately protected as dramatic works, and remain so for quite some time, as we shall see.

The last change of relevance is that under the 1956 Act still photographs were instead protected for 50 years after the end of the year in which there were first published. This inadvertently resulted in unpublished photographs having an indeterminate – and possibly perpetual – term of protection. The first owner of the copyright in a photograph was also changed to whoever commissioned it.

Crucially, however, the new legislation on still photographs was not retrospective, and the Act specifically states that photographs created before it became law remained protected under the terms of the 1911 Act, i.e. creation plus 50 years and initially owned by the owner of the camera. In practical terms this mean that any photographs taken on or before 31 May 1957 would expire at the end of 2007 at the latest, whilst only those taken and published after that date where protected for publication plus 50 years, with those taken and unpublished having an indeterminate term.

A period of 45 years separated the 1911 and 1956 Acts, but the next major change in UK copyright legislation would only take another 32 years.

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (the “1988 Act”), as the name suggests, had a much wider scope than copyright alone. For dramatic works the term of protection remained as the last co-creator to die plus 50 years, but the composer [and lyricist] of original music forming part of the work was now counted as a co-creator.

The vast majority of Hitchcock’s films were unaffected, but five had their terms extended on account of their composers being the last co-creator to die, these being Spellbound, Notorious, Topaz, Frenzy, and Family Plot. The latter is of particular note, in that John Williams is still alive, so the year in which the 1988 Act term would have expired is not yet known.

The idea of a film being protected as a physical object was retained, although the 50-year term was now calculated from the end of the year in which it was released, or if unreleased, the year it was made.

Copyright on still photographs was changed to run for 50 years from the end of the year in which the photographer died, with they themselves being the initial owner of the copyright. Again, though, this was not retrospective, and only applied to photographs taken after the new legislation became law on 1 August 1989. Photographs taken before that date were stated as having the same protection as they had under the 1956 Act, and therefore by implication the 1911 Act for any photographs taken before 1 June 1957. The issue of potential perpetual copyright on photographs taken between 1 June 1957 and 31 July 1989 but not being published was addressed by giving them a term of protection of 50 years from the end of the year in which the new legislation became law, i.e. to the end of 2039.

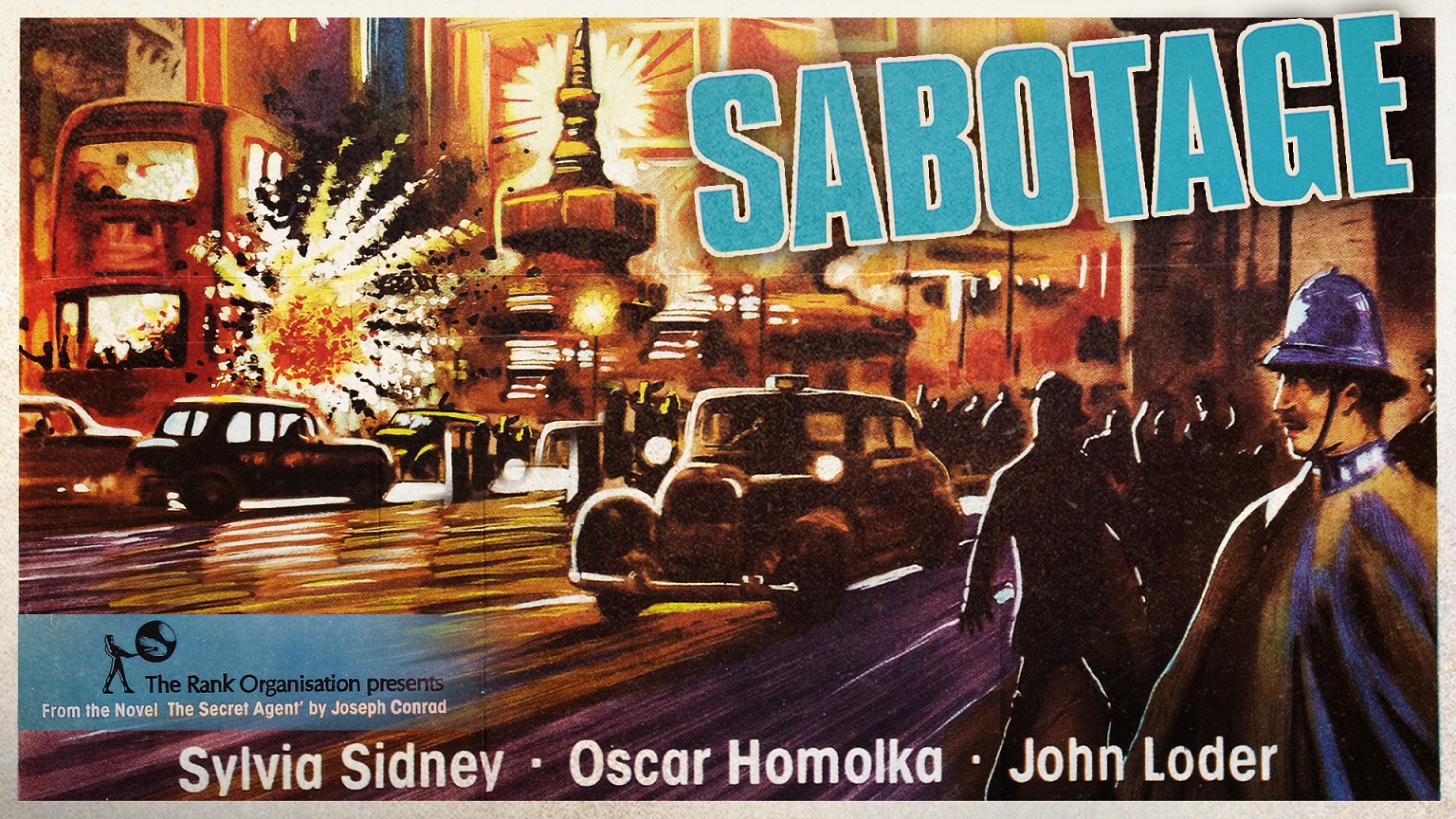

John Loder and Sylvia Sidney in Sabotage

The Duration of Copyright and Rights in Performances Regulations 1995

The most recent change to UK copyright law was a Statutory Instrument – The Duration of Copyright and Rights in Performances Regulations 1995 (the “1995 SI”) – intended to harmonise most terms of protection across the European Union, which automatically bumped the 1988 Act’s 50-year posthumous terms to 70 years. Controversially, this included a provision to revive such 50-year copyrights that had previously expired. The scope for this to happen with films was extremely limited, given that few if any had expired between 1976 and 1995, but certainly the novels of some well-known authors were affected. Virginia Woolf, for example, had died in 1941, so the copyright on her published books had expired at the end of 1991, but the 1991 SI revived and extended it to the end of 2011 – an unexpected windfall for her heirs!

For films the expected copyright expiry dates were increased by two decades, meaning that Hitchcock’s will now not start falling into the UK public domain until the end of 2050 at the earliest, with the last being Family Plot some time after the end of 2088 at the earliest, for the reason already stated.

National Archives: Copyright and Related Rights | Duration of Copyright flowchart

Crown Copyright

Although not quite unique, Hitchcock’s works do include two rare exceptions to the foregoing in the form of his two French-language shorts – Bon Voyage and Aventure Malgache – commissioned during the Second World War by the Ministry of Information, which thus fell under Crown Copyright. Whilst earlier legislation was more generous to Crown Copyright, the 1988 Act sets it for dramatic works as 50 years from the end of the year in which a work was commercially “published,” a term that was not affected by the 1995 SI.

Neither film was released during the war and in fact were not made available to the public until being first sold on VHS by Milestone Films in the US and by Connoisseur/BFI in the UK in 1994. They were also first screened by BBC2 in September 1994. As these releases are recognised as publication for the purposes of British law, the films will enter the UK public domain after the end of 2044.

How to make a crowd seem bigger than it is in sunny Middlesex! Hitchcock (leaning on rail) directs a crowd scene for Sabotage (1936) on the Gaumont British lot at Eastcote Lane in Northolt. His wife Alma Reville and their daughter Pat can also be seen, standing between the two policemen flanking young Stevie. The UK copyright on this photograph expired at the end of 1986, but the final form of the contents of the film camera seen in it remain protected until the end of 2065 in the UK, and 2031 in the US.

[1] Generally, copyright commentary talks of “co-authors,” but this is obviously open to misinterpretation, so I use the broader “co-creators.”

Alfred Hitchcock: Dial © for Copyright, Part 2

Nick Cooper © 2018. Other works:

- Things to Come (1936) BD/DVD and DVD (region B/2)

- London Underground at War (2014)

- City on Fire: Kingston upon Hull 1939-45 (2017)

Related articles

- Alfred Hitchcock Collectors’ Guide: Setting the Scene

- Part 2: British Film Restorations and Collections

- Alfred Hitchcock Collectors’ Guide: Miscellaneous British Films

- Free the Hitchcock 9! Releasing the BFI-Restored Silents on Home Video

- Bootlegs Galore: The Great Alfred Hitchcock Rip-off

- Alfred Hitchcock: Dial © for Copyright: British Law

- Hitchcock/Truffaut: The Men Who Knew So Much

- Alma Reville: The Power Behind Hitchcock’s Throne

- Alfred Hitchcock Collectors’ Guide: The British Years in Print

- Part 2: Best of the Rest

- Alfred Hitchcock: The Dark Side or the Wrong Man?

- Alfred Hitchcock Collectors’ Guide: Miscellaneous Releases

- Beware of Pirates! How to Avoid Bootleg Blu-rays and DVDs

- Charlie Chaplin Collectors’ Guide, Part 2: The Bad, the Ugly and the Good

For more detailed specifications of official releases mentioned, check out the ever-useful DVDCompare. This article is regularly updated, so please leave a comment if you have any questions or suggestions.

An infinitesimally tiny quibble when set against what is otherwise a magnificent piece: the two French wartime shorts, Bon Voyage and Aventure Malgache, were actually first screened to the public in September 1993, courtesy of Hampstead’s Everyman Cinema. And I seem to recall (I was involved with this presentation and the accompanying early Hitchcock season) that the BFI told us with regard to whether or not we could legitimately market them as Hitchcock premieres that only one of them was actually a public premiere, although annoyingly I’ve forgotten which one. So presumably “publication” should date from 1993 – or, potentially… Read more »